By Richard J. Ablin, Ph.D, and Bernadette Greenwood, BSc, PG Cert., RT (R),(MR)(ARRT)

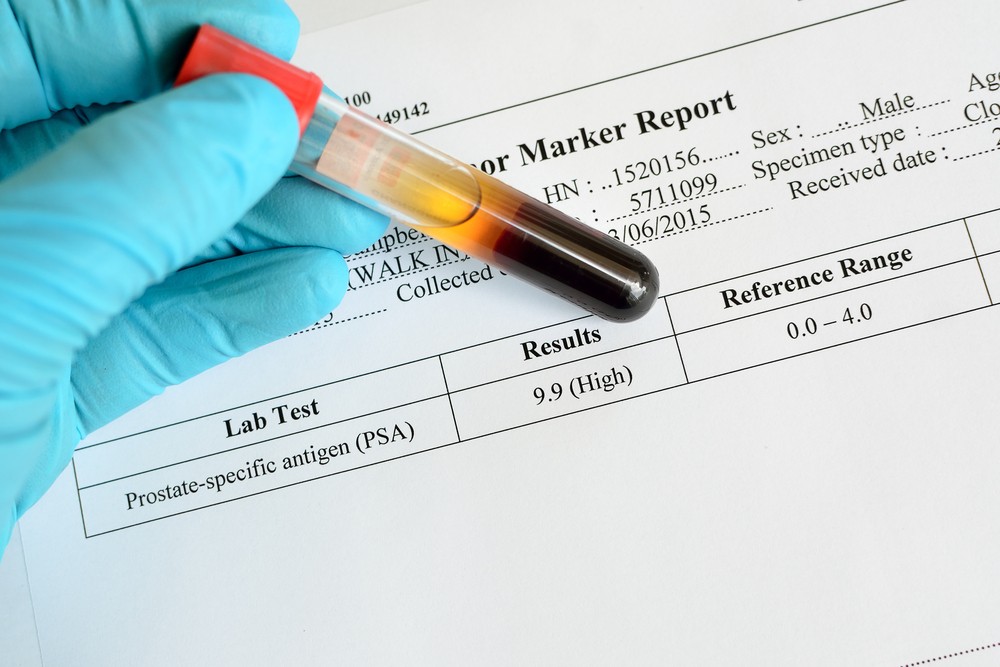

Sixteen years after the approval and use of the prostatespecific antigen (PSA) test for generalized population screening by the FDA, an opinion editorial in The New York Times by the discoverer of PSA (and co-author of this article), Richard J. Ablin, directed attention to the shortcomings of the PSA test contributing to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer (PCa).

PSA testing further came under re when the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force gave it a “D” rating citing that the harms outweigh the bene ts. This meant that they did not recommend PSA for generalized screening for PCa.

Nearly everyone agrees that screening for any disease should be a shared decision between the patient and their practitioner. In the wake of the “D” rating, screening slowed and subsequently, a suggested surge in new cases of advanced PCa was observed. Physicians, patients and advocates responded and the rating was recently changed to a “C” for men ages 55-69 years but remains a “D” for those 70 and older.

So what is the happy medium? Is there a balance between overdiagnosis and overtreatment?

First, we should understand that PSA is not specific for prostate cancer; it is specific for the prostate gland and may therefore be clinically useful in detecting abnormalities of the prostate such as prostatitis (an infection), benign prostate hypertrophy (an enlargement), and/or cancer.

Second, the PSA blood test is used:

The first question should be “What is the prior probability of disease?” In other words, what is the likelihood a man bears a risk for prostate cancer? Family and clinical history can steer patients and clinicians toward screening where warranted. If, for example, a man has a father who died from PCa and a brother who also has it, PSA screening would be beneficial. Ethnicity may also have a bearing on screening choices as African American men have a 2.5 greater risk of death from PCa compared to their Caucasian counterparts.

Other calculations derived from PSA, often referred to as PSA-related concepts, can be helpful to make clinical decisions such as PSA velocity (PSAV), the PSA value over time when tested serially, and PSA doubling time (PSADT) which can also be an indicator of either a non-aggressive or aggressive disease of the patient.

Another PSA-related concept is PSA density (PSAD), the PSA (in ng/mL) divided by gland volume (in cc), which can be a helpful indicator of disease potential. If two men both have a PSA of five and one has a gland volume of 80 cc and the other has a gland volume of 35 cc, their PSADs are 0.063 ng/mL/cc and 0.143 respectively. Because of the larger gland volume of the first man, the concentration of PSA is lower; because of the smaller gland volume of the second man, the concentration of PSA is higher.

So regardless of what you hear on the news or outside your doctor’s o ce, know that PSA, if used within the proper context and with other diagnostic tools, can be a helpful biomarker for prostate gland abnormalities, including the detection of PCa and its clinical management.

Dr. Richard J. Ablin is a professor, Department of Pathology, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Arizona Cancer Center and BIO5 Institute, and author of The Great Prostate Hoax: How Big Medicine Hijacked the PSA Test and Caused a Public Health Disaster. Bernadette Greenwood is Clinical Instructor, UC Riverside School of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine. For more information visit www. DesertMedicalImaging.com.